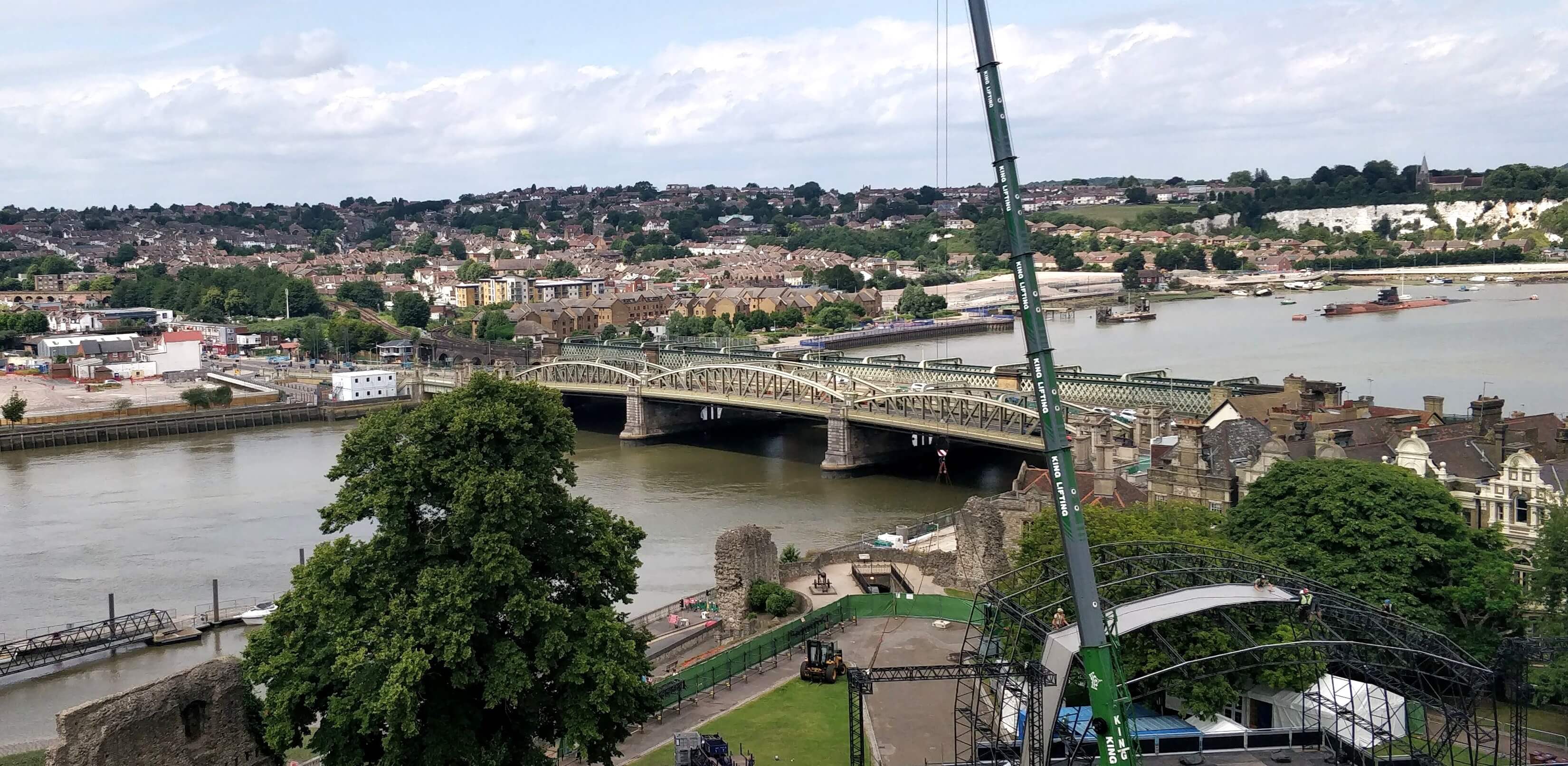

Rochester Castle

“Living memory does not recall a siege so fiercely pressed and so staunchly resisted.”

In 1215 England was wracked with civil war.

King John’s barons had taken up arms against him. London, held by the rebel barons, was surrounded by a ring of castles including Rochester, which was held by the archbishop of Canterbury. The constable of the castle, sympathetic to the barons, opened his gates*1 to a small contingent of rebel knights, led by William d’Aubigny. Unfortunately for the small force of at most 140 knights*2, the king was not far behind, and by October 1215 the king’s army had arrived.

John was not a popular king, but he was not without tactical ability. On arriving in Rochester he sent fire ships to block supplies coming down the Medway, and quickly took the bridge into the town. The rebels sent a small force out under Robert Fitzwalter out to retake the bridge, but to no avail. John quickly set about with his usual vindictive style, ransacking the cathedral and stabling his horses there as vengeance for the archbishop ceding the castle to the rebels. The rebels now trapped within the walls of the castle, he began to construct five trebuchets. John kept the trebuchet bombardment going day and night, and began undermining the outer wall. A breach was made*3 and by November John held the outer walls, forcing the rebels back into the keep.

The rebels surrounded

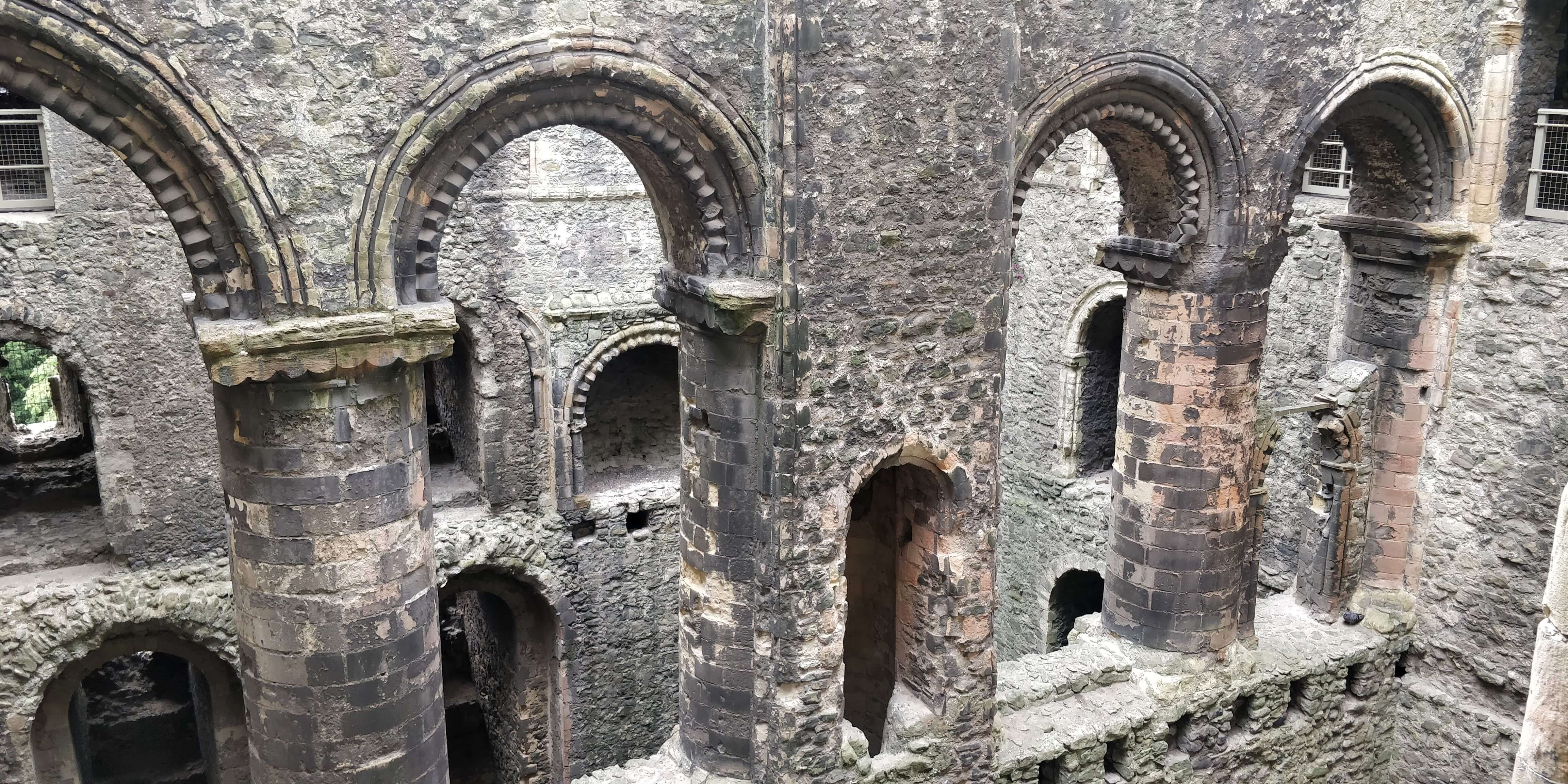

The keep at Rochester is a formidable structure. Its walls are almost 4 metres thick, and it stands 34 metres tall. It is divided into two halves by a great crosswall, and has a gatehouse-like structure attached to the front.

In order to assault the gate, attackers would have had to climb the stairs in full view of the defenders, cross a narrow bridge, and then break the gate, before storming the gatehouse and breaking the inner gate. Even then those attackers would have only breached half of the keep.

The challenge did not daunt John, and he began the trebuchet bombardment once again.

And yet the walls were not breached. And the garrison, though running out of supplies, believed they would be relieved so they held out. In fact a force of 700 rebel horsemen did ride to their relief from London, but saw John’s army and turned back.

The rebels were on their own.

“Bring fire beneath the tower”

John decided to change strategy. He ordered his miners to begin undermining the keep, around the south east tower. The foundations were deep, and the miners had to avoid the old roman walls of Rochester, but eventually the tunnel was complete, with only wooden pit props holding up the south east tower. King John wrote to Hugh de Burgh, his justiciar (a kind of chief official), “send to us with all speed by day and night forty of the fattest pigs of the sort least good for eating to bring fire beneath the tower”. John’s men slaughtered the pigs, and poured the fat into barrels which were stacked in the tunnel*4.

A fire was lit and the pit props collapsed.

The south east tower split in two with a great rending crack before collapsing, taking some of the walls with it. Perhaps testament to how formidable a castle Rochester was, the king still did not storm the keep, instead waiting for the defenders to begin to starve, forcing them to surrender. One chronicler tells us that John wanted to execute all of the defenders, but was convinced out of it by one of his captains. Instead he imprisoned most of them, barring a crossbowman who had served the king all his life before defecting.

Within a year, the castle would be retaken by the rebels under Prince Louis of France, and not long after that, John would be dead.

I think this siege stands testament to the hatred both sides had for each other by late 1215. As the Barnwell chronicler tells us, “living memory does not recall a siege so fiercely pressed and so staunchly resisted”. But it also shows a change in siege warfare and castle building in England. Round towers would soon be preferred over square, and great keeps, now shown to be vulnerable, would be abandoned in favour of the grand concentric castles that Edward would build in Wales. After Rochester, to quote the Barnwell chronicler again, “There were few who would put their trust in castles”.

Notes

Note 1: It’s unclear when the knights arrived - the constable took over from the archbishop on the king’s orders in May 1215, and the siege began in October, but I’ve heard it described as the king being hot on the heels of the rebels, though I don’t know the source for that.

Note 2: Somewhere between 95 and 140 knights, plus archers and other foot soldiers - still a considerably smaller force than the king.

Note 3: The Barnwell chronicler and Roger of Wendover disagree on how the breach was made. Barnwell suggests it was made by the trebuchets, Wendover suggests a mine was used.

Note 4: This is one theory, wacky earlier theories include herding the pigs into the tunnel with flaming torches tied to them.

Sources

This great blog post.

Various wikipedia articles, here and here.

Information on the signs at the castle itself.

Marc Morris’s documentary Castle (which you can find as a book here)